eXpOS File system and Implementation Tutorial

It is necessary to read the following documentations before starting with this tutorial.

1) User level view of eXpFS file system.

2) Program level interface to different file system calls.

3) Read about file permissions.

To implement the file system, one needs to understand the file system data structures that the OS maintains. One should also understand how various file system routines of the OS access and update these data structures.

There are two categories of file data structures. The first category consists of data that remains in the disk even when the machine is shut down (disk data structures). These are described first:

1. Disk blocks and Disk Free List

The data of a file is stored in disk blocks. A file may have up to 4 blocks of data. The OS provides the user with an interface where the user feels that the file is sequentially stored although the actual allocation could be in non-contiguous disk blocks. The Inode table entry (described next) for a file stores the block numbers of the disk blocks which contain the file data.

The disk free list is a global disk data structure that indicates which disk blocks are allocated and which disk blocks are free.

Disk blocks are allocated for a file by the Write system call. When a user program issues a write request, the system call allocates new blocks whenever necessary. (In more detail, the Write system call routine invokes the Get Free Block function of the Memory Manager Module to allocate a disk block.) Disk blocks associated with a file are de-allocated when the file is removed from the file system by the Delete system call (by invoking the Release Block function of the Memory Manager Module.) Whenever blocks are allocated/released, the disk free list is also updated to indicate the allocation status.

The following disk data structures contain meta-data corresponding to each file in the system. Inode table and the root file are data structures of this kind.

2. Inode Table

Inode table is a global data structure that contains an entry for each file stored in the file system. When a file is created using the Create system call or loaded into the disk using XFS-interface, a new Inode entry is created for the file. The inode entry of a file stores the following attributes of the file: 1) filename, 2) file size, 3) user-id of the owner of the file, 4) file type (data/executable/root), 5) file access permissions and 6) the block numbers of the disk blocks allocated to a file (maximum four blocks).

When a file is created by the Create system call, no disk blocks are allocated for the file, and only an Inode entry is created. Hence the file size will be set to 0 initially. Filename and access permissions are supplied as arguments to Create system call and are set accordingly. eXpOS allows only data files to be created using Create system call. Hence, the file type of any file created using the Create system call will be set to DATA. (Executable files can only be externally loaded into the file system using xfs-interface). The user-id of the process executing Create system call will set as the owner of the file. (The user-id of a process is the user-id of the user logged into the system currently. eXpOS is a single terminal system. Only one user can login into the system at a time and run user processes).

As noted previously, as data is written into the file by the Write system call, new disk blocks may be allocated. Whenever a block is allocated for a file, the block number is recorded in the Inode table.

A file can be created with Exclusive Access / Open Access permission. The access permission is given as an argument to Create system call. If a file is created with exclusive access, the Delete and Write system calls must fail if executed by any process whose user-id is not equal to root, or the owner of the file. In other words, other users except the root shall not be permitted to modify or delete such files. When a file has open access permission, all users are allowed to perform any operation on the file.

3. Root File

The root file stores human readable information about each file in the file system. The eXpFS file system does not support a hierarchical directory structure and all files are listed at a single level. Each file has an entry in the root file. The kth entry in the root file corresponds to the file whose index in the Inode table is k. The root file entry for a file contains filename, file size, file-type, user-name and access permissions. Thus, part of the the data in the Inode table is duplicated in the root file. The reason for this duplication is that root file is designed to be readable by user programs using the Read system call (unlike the inode table, which is accessed exclusively by OS routines only). An application readable root file allows implementation of commands like “ls” (see Unix command “ls”) as user mode programs. Write and Delete system calls are not permitted on the root file.

The only data in the root file entry of a file that is not present in the inode table is the user name of the owner of the file. The inode table entry of a file contains a user-id of the owner. The user-id value can be used to index into the user table (described below) to find the username corresponding to the user-id.

When a file is created, the Create system call must initialize the root file entries of the file along with the Inode table entries. Similarly, when the file size is changed in the Inode table by a write to the file (in the Write system call), the file size value in the root file also needs to be updated.

4. User Table

User table contains the names of each user who has an account in the system. Though user table is not a data structure associated with the file system, one needs to understand a little bit about this data structure for the file system implementation. The details of how and when user table entries are created are not relevant to the file system implementation.

For the present purpose, it suffices to understand that each user has an entry in the user table. The entry for a user in the user table consists of a) username and b) encrypted password. The OS assigns a user-id to each user. The user-id of a user is the index of the user’s entry in the user table. The first two entries of the table (corresponding to user-id 0 and 1) are reserved for special users kernel and root.

When a process executes the Create system call to create a file, Create system call looks up the process table entry of the calling process to find the user-id of the process executing Create and sets the user-id field in the Inode table. The system call then looks up the user table entry corresponding to the user-id and finds out the username and sets the user name field in the root file entry created for the file.

The second category of data structures are transient - they are "alive" only when the OS is running (in-memory data structures). These data structures are described below:

When the OS is running, user processes can Open/Read/Write an already created file. When a file is opened by a process using the Open system call, a new “open instance” is created. The OS keeps track of the number of open instances of a file at all times. If a file is opened multiple times (by the same or a different process), each Open call results in creation of a fresh open instance.

Associated with each open instance of a file, there is a seek pointer, which is initialized to the beginning of the file (value 0) by the Open system call. Whenever the file is read from/written into, the update is done to the position in the file corresponding to the seek value, and the seek value is incremented. If a process opens a file and subsequently invokes the Fork system call, the seek pointer is shared between the parent and the child. Hence, subsequent to the fork, if either the parent or the child executes Read/Write system call on the open instance, their common shared seek pointer advances. Finally, the (shared) seek pointer value can be modified (by either process) using the Seek system call. This is the mechanism through which the OS allows multiple processes to share access to a file.

Suppose a process closes an open instance using the Close system call, the Close system call first checks whether the open instance is shared by other (child/parent/sibling) processes. In that case, the OS simply decrements the “share count” of the open instance. If the last process that shared an open instance closes the file, then the share count reaches zero and the open instance is closed.

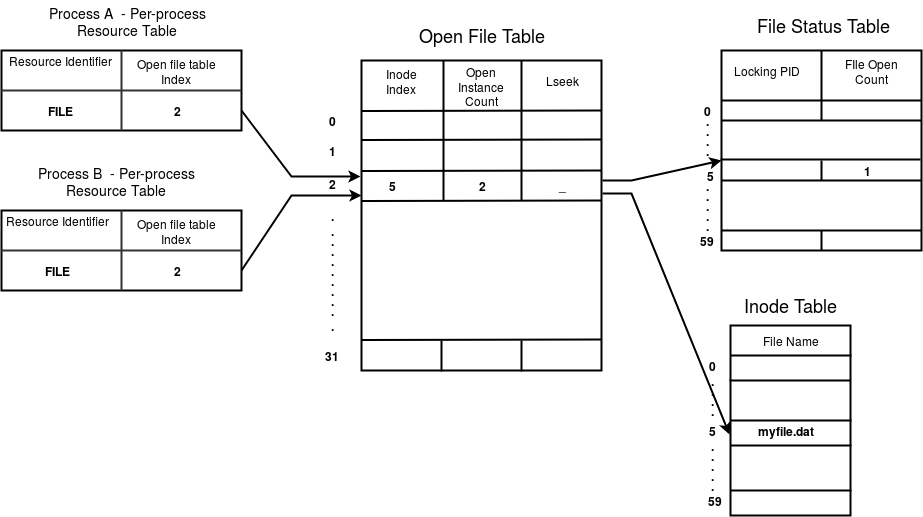

To implement this somewhat intricate file access and sharing mechanism, the OS maintains two global file data structures - the file status table (also called the inode status table), and the open file table. Moreover, for each process the OS maintains a per-process resource table, which contains information pertaining to the open instances of files of the particular process.

The OS further maintains a buffer cache which is used for caching data blocks of files in current use. A buffer table is used to manage the data related to the buffer cache. These data structures are described below. Read the description of open file table and file status table before reading further.

1. File (Inode) Status Table

File (Inode) status table contains an entry for each file in the file system. The index of a file’s Inode table entry and file status table entry will be the same. That is, if a file’s entry occurs - say - 10th in the inode table, its entry in the file (inode) status table will be the 10th one as well. The purpose of the table is two-fold 1) To keep track of how many times each file has been opened using the open system call. 2) To provide a mechanism for processes to lock a file before making updates to the file’s data/metadata.

Every time a file is opened by (any) process using the Open system call, the file open count field in the corresponding file status table entry is incremented. Thus, the table gives the global count of the number of open instances of a file.

Second, when a process enters a file system call and tries to access a file, the system call code must first lock access to the file to ensure that till the system call is completed, no other process is allowed to execute any file system call that accesses the file’s data/metadata. This is necessary to ensure safety under concurrent execution. The system call locks the file by setting locking-PID field of the file status table to the PID of the process executing the system call. Upon completion of the system call, the system call code must unlock the file before returning to user mode. The Acquire Inode and Release Inode functions of the Resource Manager Module are designed to handle file access regulation (locking).

The SPL constant FILE_STATUS_TABLE is set to the beginning address of the file status table in memory (see memory organization).

2. Open File Table

As noted earlier, If a process opens a file using the Open system call and subsequently execute a Fork system call, the open instance of the file is shared between the parent and the child. If the child (or the parent) further execute fork, more processes will share the same open instance. Hence, there must be a mechanism to keep track of the count of processes sharing the same open instance of a file. Open file table is the data structure which keeps track of this count.

Whenever a file is opened by a process, an open file table entry is created for the open instance. The entry contains three fields:

a) The index of the inode table of the file.

b) The count of the number of processes sharing the open instance, which will be set to 1 when the file is opened as only one process is sharing the open instance. When the process executes a Fork system call, the share count is incremented to reflect the correct number of processes sharing the open instance. (Note: Do not confuse this count with the file open count in the file status table.)

c) The seek pointer for the open instance is stored in the open file table. Any read/write operation on this open instance must read from / write into this position of the file and advance the pointer. When a file is opened, the seek position is set to 0. Note that the seek pointer is shared between all processes sharing the open instance.

The SPL constant OPEN_FILE_TABLE is set to the beginning address of the open file table in memory (see memory organization).

When a process executes a Read/Write system call on an open instance, the system call handler, along with the data read/write operation on the file, advances the seek pointer in the open file table entry corresponding to the open instance.

3. Per-Process Resource Table

When a process opens a file, a new entry is created for the open instance in the per process resource table of the process.

This entry contains two fields:

a) A flag indicating whether the entry corresponds to a file or a semaphore.

b) Index of the open file table /semaphore table entry of the open file / semaphore instance.

Here we will be concerned only about the case when the entry corresponds to an open file.

The Open system call returns the index of an entry in the resource table as the file descriptor to the user. Any Read/Write/Seek/Close system call on the open instance of a file must be given this file descriptor as the argument. Read/Write/Seek/Close system calls use the descriptor value passed as argument to identify the open instance (determined uniquely by the open file table index associated with the file descriptor). When a process forks a child, Fork system call copies the entries of the resource table of the parent to the resource table of the child. Thus, the child inherits the open instances of files from the parent.

As an example, consider the following scenario. Let process B be a child of process A. Assume that an open instance of a file by name myfile.dat be shared by A and B. Suppose the inode index of myfile.dat is 5. Assume that the open file table index for the open instance is - say 2. The following figure shows the various table entries for the open instance.

In addition to the above data structures, the OS maintains the following global data structures:

4. Memory buffer Cache

Whenever a process tries to Read/Write into a file, the relevant block of the file is first brought into a disk buffer in memory and the read/write is performed on the copy of the block stored in the buffer. The OS maintains 4 memory buffer pages as cache (and will be numbered 0,1,2,3. The buffers are in memory pages 71, 72, 73, 74 - see memory organization). A simple buffering scheme will be used here. When there is a request for the ith disk block, it will be brought to the buffer with number (i mod 4). If the buffer is presently containing another disk block, then the OS must check whether the disk block needs a write-back (dirty) before loading the requested block. This will be described soon.

5. Buffer Table

The buffer table is used for managing the buffer cache. The table contains one entry per each buffer page. The entry for a buffer contains:

a) The block number of the disk block currently stored in the buffer page. If the buffer is

unallocated, the disk block number is set to -1.

b) A flag indicating whether the block was modified after loading (dirty).

c) The PID of the process that has locked the buffer page. (-1 if no process has locked the

buffer.)

The locking PID field requires some explanation. When a process tries to do read/write into certain data block of a file using Read/Write system call, the system call must first determine the buffer number to which the block must be loaded (using the formula indicated above) and lock the buffer before initiating disk to buffer data transfer. This is to prevent other processes from concurrently trying to load other blocks into the same buffer page.

To understand the dynamics of how file system calls operate with the above data structures, let us consider an example. Suppose a process executes a Write into the open instance of a file. The Write system call uses the file descriptor (received as input argument) to find the index of the open file table entry corresponding to the descriptor. From the open file table entry, Write gets the seek pointer (using open file table) and index of the the inode table entry for the file. Next it locks the Inode (using Acquire Inode function of the Resource Manager Module). It then determines the disk block to which data must be written (using the seek position and the Inode table entry of the file). Now, Write invokes the Buffered Write function of File Manager Module to perform the write.

Buffered Write first calculates the buffer number corresponding to the block number and locks the buffer (invoking the Acquire Buffer function of the Resource Manager Module). It then checks whether the disk block to be written into is already present in the buffer. If not, the disk block has to be loaded first into the buffer. However, if the buffer is currently containing another disk block and if the disk block is dirty, then the disk block must be written back first. The buffer table entry for the buffer will help Buffered Write to determine whether the buffer is free, or if not free whether write back is required. Write Back is performed using the Disk Store function of the Device Manager Module. (Disk Store function makes another resource lock - calls the Acquire Disk function of the Resource Manager Module before disk commit is done).

Finally, after getting the buffer page free for use, Buffered Write brings the required disk block into the buffer page using the Disk Load function of the Device Manager Module. Now Buffered Write can write the data into the buffer. Since the contents of the block has been modified, Buffered Write sets the dirty bit in the buffer table entry for the buffer. Note that Write does not store the modified buffer back to the disk. The modifications are committed only when a subsequent write operation requires the buffer to be loaded with a different disk block. The OS also commits back all dirty buffers to the disk before shutdown.

A Read operation is similar, except that the dirty bit is not set as the page is not modified.

The execution of Read/Write system calls involves a sequence of resource acquisitions - namely inode, buffer and disk. The resources are acquired in the order Inode-buffer-disk and must be released in the reverse order when the actions are completed. This avoids circular wait - a sufficient condition for deadlock prevention.

6. In-Memory Copy of Disk data structures

Finally, the OS maintains an in-memory copy of all the disk data structures - viz., inode table, user table, root file and the disk free list. While the OS is running, a new user could be created or a file could be created/modified/deleted. In such cases, the update is made into the memory copy of the corresponding data structures and not the disk copy.

The OS must write back the memory copy of all disk data structures and all dirty buffers to the disk before the system is shutdown. The file system implementation described here is not crash resilient. This means, if the OS crashes before (or during) such write back, the memory-copy to disk updates may be partial and the disk data structures may end up in inconsistent state. In such case, one or more files may be corrupted and the disk may require reformatting.